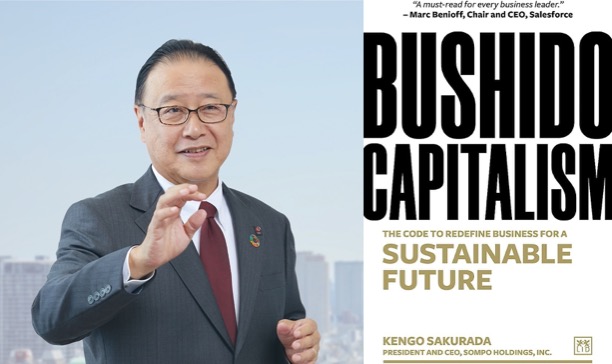

About the Author: Kengo Sakurada is Chairman/CEO of Sompo Holdings, Inc., a Nikkei 225 company, and President/Group CEO of Nksj Himawari Life Insurance Company. He also serves as chairman of Keizai Doyukai, the Japan Association of Corporate Executives.

The Bushido code is made up of justice, courage, benevolence, politeness, veracity, honor, loyalty and self-control.

More than 100 years ago, a Japanese educator and economist wrote Bushido: The Soul of Japan, about the code of the samurai. He suggested the code could inform other professions. If businesses today would adapt the Bushido code to contemporary times, it could provide structure and moral guidance for steering capitalism to solve some of the most vexing international problems.

The modern world offers an infinite number of choices and instant gratification. Modes of doing business have changed rapidly, and few of today’s most successful companies existed at the turn of the 20th century.

“Capitalism has lifted countless people out of poverty. Yet it remains incumbent upon us not to allow those stories of heartening success to distract us from the urgent work – and the moral obligation – we face today.”

During the 1900s, a “great acceleration” brought massive changes in communication, technology and travel, as well as rocketing growth in the stock markets. While these developments included praiseworthy advances, this surge had a dark side, too, such as the unequal distribution of wealth.

Capitalism is unsustainable without redefinition and reformation. Business leaders must not prioritize profit over the environment, inequality, and employee physical and mental health. The old metrics for performance and success demand re-examination and may, in fact, contribute to the world’s problems.

For example, GDP does not measure destruction of the environment or depletion of resources. As long ago as 1968, Robert F. Kennedy noted that the US Gross National Product included advertising for cigarettes, ambulances for traffic accident injuries, measures to prevent burglaries and prisons for the burglars who got past them. In brief, GDP includes all the ways in which social ills contribute to growth.

The Bushido value of justice calls for businesses to be responsible.

Bushido’s fundamental virtue – justice, or rectitude – informs the Japanese principle of Sampo-Yoshi, which holds that businesses should anchor their success in responsibility. Success helps the seller, the buyer and society at large. The ancient samurai could not compromise on this virtue, and neither should contemporary business leaders. Concern for community well-being should be a foundational ethos of corporate beliefs.

“Success through responsibility…means achieving three-way satisfaction: it is advantageous for the seller, but also for the buyer and for the broader society.”

The great acceleration took a severe toll on the environment, as carbon emissions escalated dramatically and people consumed natural resources on an unprecedented scale. Greta Thunberg, a Swedish teenager who addressed the World Economic Forum in 2019, exemplifies a new generation of brave young activists who are passionate and resolute about changing the world for the better.

The Bushido view of courage differs strongly from bravado.

The second Bushido virtue, courage, relates closely to justice. Courage means calling right and wrong what they are. Under this principle, business leaders must remain steadfast – and be brave enough – to support regulations and practices for the greater good. It takes courage to be a whistleblower, for example, and it takes courage to admit your mistakes and shortcomings.

In today’s business world, benevolence implies empathy and care, even tenderness.

Benevolence, the third virtue of Bushido, includes compassion, a virtue that seldom appears in corporate boardrooms, where the loudest applause goes to fierce and resolute competitiveness, machismo and Machiavellianism.

The well-being of your staff and community is critically important. The Japanese concept of Pin-Koro prizes a full, long life that ends happily with a quick death. Yet in contemporary Japan, some employees work themselves to death. Japanese companies tried to address this problem by giving people incentives to take breaks for the sake of their health.

“As business leaders, we can no longer blindly chase profits if that means exacerbating a raging climate crisis. We have a duty to help solve the deep and harrowing problems of inequality. We must be held accountable when it comes to the physical and mental health of our labor forces.”

Employees compete with their colleagues and with machines that can carry out some – if not all – of their functions. They fear that technology will take over millions of jobs. Meanwhile, mental illness rises globally, at a cost to the global economy that could reach $16 trillion. Economic ambition may not be responsible for all of this, but these trends are related.

Business leaders generally don’t understand how the needs of their employees are changing, and how their companies should take care of their people. An aging workforce raises serious implications, even though older people are deciding to work longer – in part, due to longer life expectancies and education, but also due to financial pressure. Managers must balance their need to recruit techy young people who are curious about the world with their simultaneous need to retain older workers’ knowledge and experience.

The pandemic caused a “forced pause,” but companies and workers responded with adaptability.

The way national economies became closely linked during the great acceleration brought enormous efficiencies but showcased new vulnerabilities. Amid that momentum, an issue of The Wall Street Journal in January 2020 gave only one short paragraph to news of an emerging virus in central China. More important issues dominated the headlines, such as US relations with Iran and unrest in Hong Kong. Few people

paid immediate, close attention to this new virus. But during the ensuing weeks, reports of outbreaks accumulated and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, confirming more than a million cases globally by March of that year.

The pandemic caused a “forced pause,” disrupting businesses, driving employees to work remotely, and disproportionately affecting women and those working low-level jobs.

“While the pandemic seemed to transform the way we live, work, consume and socialize, it was not in itself a cause of great change; rather, it was a catalyst.”

The COVID pandemic provided all the factors that lead to recession, including shocks to consumer demand, supply lines and the financial system. However, the forced pause also proved that people are extraordinarily adaptable, as employers and employees transitioned to remote work practically overnight, and science produced effective vaccines within a year.

APoliteness and veracity point the way for reordering society.

Politeness relates to benevolence, though “respect” might be a better word, because refocusing capitalism and adapting commerce to today’s world demands it. All stakeholders should give and receive authentic courtesy and consideration. The lowest person on the corporate ladder merits as much respect as the highest.

Veracity, the fifth virtue of Bushido, translates as truthfulness and authenticity, and aligns with courage. Among other things, veracity means neither minimizing nor exaggerating your talents. It includes acknowledging your limits and errors. Leaders with veracity admit they are sometimes weak and need help.

“As the coronavirus spread, it quickly became apparent that business leaders who were ignoring health protocols in the interest of chasing economic gains were playing with fire.”

The word “purpose” has become a cliché in contemporary usage. Company mission statements often refer to firms as “purpose-driven,” but few people consider the real meaning of this phrase. The purpose of all business should be to improve the quality of human lives. Businesses can contribute to the general welfare, but only if they reject their singular focus on short-term shareholder value. Being charitable and being profitable are not mutually exclusive.

The US Army War College has an acronym for today’s tumultuous world: VUCA, which stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. Populism, Brexit, the pandemic and authoritarianism exemplify today’s VUCA society. Better times may lie ahead, but when they arrive, people must recall the difficult times and their daunting events when the path forward was unclear – such as after the tsunami and earthquake that struck Japan in 2011.

The Bushido interpretation of honor covers many other virtues, including loyalty.Add Your Heading Text Here

Those who practice the sixth Bushido virtue, honor, also practice and value the other Bushido values. The interval from the forced pause to the great acceleration occasioned “creative destruction,” in the words of Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. Such destruction offers opportunities to reflect on the traditional limits of capitalism and to re-examine its values and goals. For example, profit driven, short-term thinking is all too common among CEOs, who willingly sacrifice long-term prosperity for immediate quarterly gains.

The seventh virtue of Bushido is loyalty, which means fidelity to a broader mission and purpose. Stakeholder capitalism should come to the fore. Such loyalty should include future stakeholders. For example, ignoring how business affects the environment is a manifestation of disloyalty to future stakeholders.

“Loyalty means being committed to the best interests of every stakeholder today, tomorrow and in years to come.”

In 1970, economist Milton Friedman wrote, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” He derided the notion of corporate social responsibility as lacking in rigor, because responsibility characterizes people, not companies. Many people in business disagree, but widespread normal practices suggest otherwise.

Still, indications of positive movement exist. For example, in 2019 the Business Roundtable acknowledged that firms should put less priority on “maximizing shareholder value.” Somewhat later, Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, wrote that his asset management firm would vote against companies whose directors and managers are inattentive to sustainability.

Self-control enables you to achieve equanimity.

The final virtue of Bushido is self-control. With it, you can gain equanimity and composure. This virtue must adapt to the contemporary environment, and it connects closely to self-awareness and emotional intelligence. It does not mean stifling your emotions, because emotions are humanizing. Suppressing them may endanger your health.

“It can be easy to fall into a trap of thinking that our small gestures and individual habits will not make an impact.”

As automation is replacing people in many roles, emotional intelligence is more necessary than ever. Science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) skills have received enormous attention because the economy rewards them more lucratively than it rewards skills in the humanities. Yet no matter how much automation accomplishes, the humanities, especially philosophy, will always be essential. Human beings are far more complex than numbers can express.

Kōnosuke Matsushita, Panasonic’s founder, was an exemplary leader who embodied Bushido.

Kōnosuke Matsushita’s family lived in poverty because his father’s commodities speculation went badly. While still in elementary school, Matsushita became an apprentice making charcoal hibachi. After that sideline closed, he became a bicycle salesman, and his entrepreneurship and discipline impressed his boss.

Matsushita saw the potential of electronics in the early 1900s, and secured employment at the Osaka Electric Light Company. He moved rapidly through the ranks, and in his spare time invented a new electrical socket. He was confident enough to quit his secure job and start his own business. Two former colleagues and

his wife’s youngest brother joined his tiny firm. Success did not come immediately. In fact, the business

was near bankruptcy when a big order came in at last. More orders followed, as did improvements in Matsushita’s products.

By 1922, he built a factory. He continued to tinker, following his interest in bicycle lamps, irons and

radios, all of which succeeded in the market. Although he was doing well commercially, Matsushita focused on his company’s purpose and put his business into a religious context – noting that as religion helps people find peace of mind, business can contribute by providing physical necessities.

“Our mission as a manufacturer is to create material abundance by providing goods as plentifully and inexpensively as tap water. This is how we can banish poverty, bring happiness to people’s lives and make this world a better place.” (Kōnosuke Matsushita)

Matsushita’s touchstone phrase was “Business is people.” Although his principles resisted militarization, World War II caused such devastation that the company had to rebuild from scratch after the war. Matsushita later established the PHP Institute; it’s acronym stands for “Peace and Happiness through Prosperity.”

Bushido drove Matsushita’s values and culture. Through thick and thin, good times and bad, he exemplified the Bushido virtues. The principles of Bushido need to be adapted to the contemporary world, which should strive for more gender and wealth equality. While businesspeople aren’t ancient warriors, Bushido virtues provide a sound foundation for ethical leadership in any era.