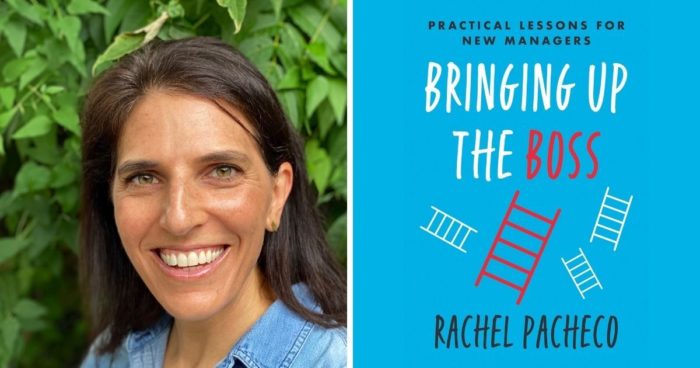

About the Author: Dr. Rachel Pacheco teaches in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania School of Education.

Most first-time managers learn to manage on the job.

Becoming a manager means taking on immense responsibility – often without adequate preparation. Few new managers have sufficient experience or knowledge to move seamlessly from doing the work to making sure the work gets done. People often earn a promotion to management based on doing a previous job well, but managing requires different skills than coding, writing reports or devising a marketing campaign. As a manager, you bear important responsibility for people other than yourself – team members whose career development, learning and daily experience of work rely a great deal on your decisions and actions.

“Managing is a muscle that needs to be built up, trained and flexed.”

As a manager, you’ll have high performers who’ll need you to provide challenging work, autonomy and responsibility to keep them engaged. And you’ll have low performers whom you must constantly coach. You’ll learn the skills and wisdom you need through experience. But this doesn’t mean you can wait to start coaching, giving constructive feedback, having difficult conversations and otherwise managing your people.

Manage team members’ performance by providing clear expectations and feedback.

Never assume a team member knows what you mean or understands how to do something. You might have skills that your reports don’t. Make your expectations crystal clear; when you fail to do so, your reports have no way of knowing what you want, and you’ll end up doing their work and thinking they’re lazy or incompetent. Employees often crave clearer directions so they’ll know what success should look like.

“Expectation setting is one of the most important things you can do to be a great manager.”

Setting specific expectations doesn’t equate to micromanaging your team. Tell your people what you want, and give them the latitude to figure out the best way to do it. Explain your goals, including specifically what you want and when you want it. If possible, provide examples. When you think you’ve explained enough, explain some more. Even after you’ve fully articulated your expectations, people might still fail. When this happens, provide objective, clear and specific feedback, ideally supported by data and examples. Give people constructive suggestions for how they can improve or change their actions and behaviors.

Avoiding constructive feedback because it’s uncomfortable or because you want people to like you amounts to managerial malpractice. In the long run, this neglect can harm your reports’ professional and

personal development, as they might not get the help and guidance they need to course correct in time. Don’t couch constructive feedback between two positives, and don’t try to soften it by making excuses for underperforming. Offer feedback concisely and as soon as possible after the behavior in question. Make your feedback session conversational, not one-way. Don’t neglect to ask your team members for their feedback on your performance. You might not like receiving constructive feedback, but you need to hear it – so ask for it, and thank people for it. Build feedback on your own performance as a manager into regular meetings and review processes. Consider sending out anonymous surveys to your people.

Direct your own learning, and coach your people to do the same.

Don’t depend on anyone else to manage your learning and career development. Support your team members in their development, but encourage them to own the process. Set your own learning goals, and work with your people to help them set theirs. Everyone’s development plan and goals will differ depending on their career aspirations, interests, strengths and weaknesses. Engage in scheduled conversations with your team members about the capabilities they want to acquire in order to reach their goals. Team members should include specific actions in their development plans that will build their skills and capabilities.

All managers can and should coach. You don’t need professional training to do so. Coaching means assisting team members to develop decision-making skills and self-awareness. Ask questions to help them work through specific situations and challenges. Avoid telling people what they should do in order to grow or meet a challenge. Instead, use coaching to build a trusting relationship with the goal of strengthening team members’ proactivity to improve their own performance and manage their own growth. While coaching, ask thoughtful, open questions. Stay curious, listen attentively, summarize salient points to make sure you understand, and plan concrete next steps with your coachee.

“Great coaching is simultaneously an art form, a scientific discipline and an innate gift. But coaching itself is a basic tool that you can start implementing immediately.”

If regular and specific feedback, coaching and performance reviews don’t adequately address a team member’s performance issues, work with the person to create a detailed performance improvement plan (PIP). The PIP should list each specific intervention and activity you intend to do together to make meaningful improvements, attached to a schedule. Don’t frame a PIP as a step toward dismissal, and don’t spring it on an employee without warning. Present it as a commitment to helping the report improve. Your prior feedback and coaching should eliminate any surprises when you begin discussing a PIP with a team member.

Inspire and motivate your team members on a one-to-one basis.

Keeping your team members engaged counts among the main responsibilities of a manager. Use the principles of human motivation – as articulated in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and other frameworks – to guide you, but realize that every person has unique motivators. You must get to know what drives each of your reports, including what they like and dislike about their work and what forms of reward and recognition they prefer.

As you get to know your reports, you will find that some are driven primarily by achievement, others by power or belonging. Achievers need frequent praise, clear goals and tangible evidence of accomplishment, such as promotions. Power-driven individuals will respond to being given autonomy, increasing responsibility and opportunities to compete. More socially driven employees enjoy engaging on tight, collaborative teams and on projects that emphasize relationship building.

“Understanding what uniquely drives your employees is critical for understanding how to incentivize, develop and structure work for your team for maximum motivation.”

Take care to set specific, time-bound, challenging – but achievable – goals with your team members. Think through the goals systematically, and calibrate expectations to avoid disappointment and bad behavior.

An outsized focus on achieving goals can lead employees to game the system or breach ethical or legal boundaries to achieve them. Keep the focus on the effort itself, not the outcome.

Learn the essentials of management.

Learn how to instill intrinsic motivation in people: Provide meaningful work; invest in people’s learning; and create shared purpose. Practice transparency, especially around how you determine pay. Develop a compensation philosophy for your team – including how compensation benchmarks against the industry, how bonuses work, the frequency of compensation reviews and how benefits are determined – and then explain it to the team. Understanding the system will help people accept compensation decisions.

“If you…are able to guide just one team member over the course of your entire career in finding their sense of purpose, you have achieved great things.”

Take care with job titles. Use them consistently, and don’t make them up as you go. Don’t use them as rewards in lieu of pay, as negotiations in the hiring process or to mollify a person you want to retain. Doing so will only create more pain when others demand the same. And it can cause a mess: If you give away a title and later recruit a truly qualified person into an equivalent role, you’ll have to demote the person already holding the title. Promote qualified people based on performance and only into real positions of greater responsibility.

Don’t suppress emotion in the office. Give people space to express themselves, and ask people how they feel. Openness lets your team members release their frustrations and other emotions. Let people bring their whole selves to work. Make people feel safe to express themselves, even if their emotional response to a situation differs from their teammates’. However, be aware that emotions, both positive and negative, can spread through a team quickly – especially when they emanate from you. Stay open and honest about your own feelings, talk to your team about the impact of emotions, and encourage discussion.

Communicate – in fact, over-communicate. You likely underestimate the need for communication, so when you think you’ve communicated enough, go ahead and repeat what you’ve said. Tell your team which information you plan to share, in what form and how often. You probably can’t share everything – such as why a person was let go, details about acquisition targets, and so on – so don’t promise full transparency. Choose your words carefully.

Employ a structured process for hiring and firing.

As a manager, you’ll be responsible for hiring and firing people. Take extreme care in doing both. Treat job candidates with empathy. Approach hiring systematically, and base decisions on qualifications, capabilities and characteristics you’ve identified as desirable – both must-haves and nice-to-haves. Follow a documented, step-by-step process. Don’t hire based on an impression of a candidate’s compatibility or culture fit. By doing so, you risk acting on biases that may favor less-qualified candidates and could suppress diversity. Conduct structured interviews. Provide guides for interviewers to ensure they ask consistent, behavioral questions of each candidate. Assess candidates objectively and fairly.

“Hiring and firing are some of the most important things you will do as a manager.”

Establish a structured process for onboarding. By quickly integrating people into the organization and your teams, you’ll build their comfort and engagement from the start. When you must release an employee for poor performance, do so only after taking thorough measures to improve performance. Let the person go clearly, without delay, respectfully and with generosity. When someone leaves voluntarily, make the person’s exit positive, conduct an exit interview, and remind the team that employees get poached based on their solid performance and learning while on the team. When you fire someone, tell the team about the efforts you took to improve the person’s performance. Should you have to lay people off, cut slightly deeper than needed and make the cuts all at once. Avoid letting people go in dribs and drabs – doing so crushes the morale and productivity of those who remain.

Build confident, collaborative teams.

Strong teams generate tremendous output and can nurture the personal and professional development of team members. Help your team members get to know each other on professional and personal levels. To build understanding and empathy among team members, use assessment tools and share them, so people can learn about one another’s preferences, strengths and personalities. Create an atmosphere of safety, so people can feel free to take risks. Build norms around how people interact. Make sure everyone gets a chance to speak in meetings. Encourage questions. Work to build community among your people.

“Make sure your team feels comfortable speaking up and speaking out.”

To avoid the powerful effects of groupthink and conformity, deliberately build a culture of inclusion and respect. Before discussing important matters, ask people to brainstorm individually. Have people share their views one by one, starting with the most junior person. Offer your own views last. Ask a member of your team to argue against the consensus opinion.

Don’t try to avoid or eliminate conflict, but promote productive conflict. Building understanding and trust within a team will help reduce relational conflict. Encourage task conflict – disagreements about what to do or how to do it – to combat groupthink. Although process conflict – over logistics, task assignments and so forth – is unavoidable, it can become frustrating and has the potential to develop into relationship conflict. To keep process conflict within bounds, have norms for resolving these disagreements, and create systems for typical situations, such as assigning meeting roles.

Manage yourself, and manage up.

As a new manager, you’ll have insecurities and fears, you’ll make mistakes, and you’ll often feel isolated and even disliked. You’ll need to manage yourself, including your mind-set and management approaches. Demonstrate vulnerability with your team. If you fake confidence, your people will know it. Build trust by admitting when you don’t know something and be willing to show your flaws, weaknesses and fears. You can maintain friendships with people who report to you if you set clear expectations, stay honest about the awkwardness of the situation and make feedback – in both directions – a frequent practice.

“You will make mistakes as a manager – and these mistakes will have far bigger consequences than the mistakes you have made in the past.”

To manage your relationship with your boss, own it. Express confidence and take the lead. Cater to your boss’s style, but set the agenda in your meetings – be proactive. When you present issues to your boss, offer a set of options to discuss. Don’t expect things to go perfectly: Even after putting everything you have into your organization, you might still miss out on a raise or promotion. If and when the time comes to move on, evaluate your options carefully. Think through what you truly want in each aspect of your next job. Tap your networks of friends and acquaintances to connect to people who could offer perspectives on a new field or leads on opportunities.