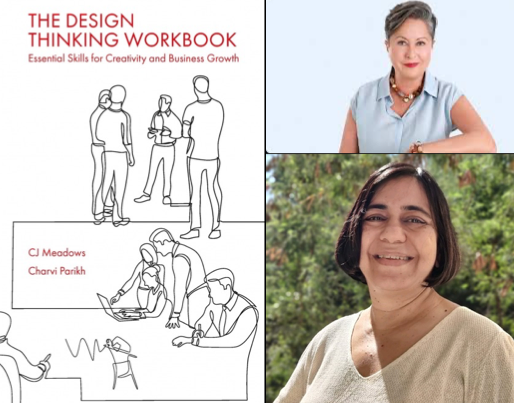

About the Authors: Charvi Parikh and Dr. C. J. Meadows are both designers and innovation consultants.

Design thinking solves human-centered problems.

While new technology, like artificial intelligence, can measure and predict human behavior, it doesn’t answer the question of why people act they way they do – such as why people buy one type of soap over another. Creating solutions that actually address human-centered problems involves designing from the consumer’s point of view.

Companies that embrace this style of design thinking grow twice as fast and receive 75% higher returns for their stakeholders. Focusing on customer insights – such as, people buy soap based on how refreshing it sounds – rather than market trends – such as, people buy a lot of colorful soap – leads to three times the “operating income” and twice the amount of “return on assets.”

“Even if you have a hammer in your hand, not all the world is a nail.”

Design thinking is a lengthy process that works particularly well in solving complex, unclear people problems. For example, if you work at a hospital and notice that patients almost never return for their follow-up appointments, design thinking can help you determine why, and how you could innovate a solution to get people to come back.

Many people have come up with different approaches to design thinking, such as the process that

involves breaking down behavioral patterns to form insights, and the IBM method that oscillates from customer observation to reflection to creation and back again. However, these approaches are most useful to experts who already know what they want and what to look for. As a beginner, it’s better to start with the basics.

Hone your empathy, observation, listening and critical thinking skills.

Before you start designing a new product or service that you think will help your customers, step back and take a look at how you perceive the world. Examine how you think about your customers, what aspects of their behaviors you focus on and how you process the insights they give you.The way you feel, watch, listen and analyze all play a major role in how you design.

For instance, some designers burn out quickly because they spend all their energy trying to meet their customers’ emotional needs, and fail to consider their own. A proper use of empathy should allow you to tap into the customer’s thoughts and points of view without becoming consumed by them. Designers who can objectively empathize create value that benefits everyone.

The opposite is true for observation – you need to go all in. Many designers hold focus groups to observe how people interact with their products. But, this setup won’t reflect real-life usage. You must go out into the field and watch how people use the product. If you were designing a new kind of bike pedal, to see how well it works, you should put it on a bike and ride down the street, because that’s what your customers will do.

“You absolutely, positively have to be there and observe!”

Once your customers come back from testing your new pedal, listen to their feedback. Don’t just listen to their words – focus on tone. Do they sound excited, confused or disappointed? Use active listening techniques, such as repeated responses or silence, to coax more information out of the customer. Think about what makes you feel heard and use that.

Take all the newly gained insights and start breaking the information down into facts, patterns and usable data. Critical thinking takes information and turns it into logical conclusions. First, ask a lot of “what if” questions that will put your product into different contexts, such as, “What if customers want to use your pedal for mountain biking?” Then, taking the data from your observations and tests, start connecting the dots and make objective judgments about what you see: For example, ”People said the pedal kept falling off, therefore it needs better screws.”

Get your creativity flowing.

A lot of design work involves using exercises to get your creative juices going. While, as a child, your imagination did most of the heavy lifting, as an adult, getting creative involves opening your mind and being curious.

“You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have. (Poet Maya Angelou) ”

One easy tool for boosting creativity is “storywording.” Originating from improv, storywording involves co-creating a story: One person starts the narrative, the next person adds a word, and so forth. Each individual builds off the others’ ideas, adding twists with every new word said. It’s an effective, and often humorous, icebreaker: People get to know one another and glimpse how each participant thinks.

Another tool you can use is the “diverge-converge” method. In this exercise, your goal is quantity over quality of ideas. Begin by writing down every possible idea in response to a challenge your team faces. The wilder, the better; remember not to judge at this point, just keep writing. Once you have at least 50 ideas, take the same amount of time it took to come up with them, and narrow them down until you have one to pursue.

If you still feel stuck, try using analogies to think about your challenge in a different light. For example, a hospital’s emergency room staff wanted to gain more efficiency in handling patients in the ER. So they spent a day at a Formula 1 racetrack, watching the pit crews. They learned how delegating certain tasks increased efficiency. Similarly, Henry Ford got the idea to break car manufacturing down into an assembly line by visiting slaughterhouses and watching how butchers cut the meat. When looking at a problem you want to solve, break it down into the attributes you think are the most important, such as speed and accuracy. Then look at other industries or jobs that excel in those attributes.

Understand your customer’s perspective.

Getting to know your customers, what they want, how they think and why they act a certain is way is imperative for successful design. Great designers spend a lot of time thinking about their products from their customers’ points of view. Without obtaining customers’ insights, you won’t know who your product will help, or how you can sell it.

“Design is the intermediary between information and understanding.” (Artist and teacher Hans Hoffman)

Start with looking for the “extreme” customers. They are the consumers that either hate or love your product. For example, if you owned a coffee house, someone who comes in every day, buys your merchandise, befriends the staff and raves about your bean selection is an extreme customer compared to a “mainstream” customer who only comes in occasionally. Extremes teach you a lot about what works or doesn’t with your product. They usually will point out their needs much sooner than regular customers, and therefore allow you to address those needs and innovate before the competition catches up.

When looking at the extremes and their needs, try using some behavioral study tools. Start with observing the customer as they interact with the product. Next, interview them to gain their opinions, emotional responses and underlying motivations. Look and listen for why they do what they do. Then, analyze. Don’t try to guide answers or ask leading questions in an attempt to prove a hunch.

Try a structured interview method: Prepare a set of questions to ask beforehand. Collect the same information from each interviewed customer, such as demographics, opinions and knowledge of the product. This way you can identify patterns with greater ease. You may also find, however, that unstructured interviews yield those magical insights that your prepared questions could have overlooked. It’s worth trying both approaches, because both can serve your goal to capture honest answers that will help you pinpoint the right problem to solve.

Identify the right problem.

If you spend months designing, building and creating a new type of smartphone holder to help people keep their credit cards, ID and phone all together only to realize that no one wants to buy it because people would rather use the AppleWallet app, then you’ve missed the real problem. Correctly identifying a problem worth solving involves truly understanding customers’ challenges at their core.

“Design is a formal response to a strategic question.” (Business owner, Mariona Lopez)

One tool you can start with is the “five whys.” This method helps find the root cause of an issue. Start with asking “why does this problem exist?” For each answer, form another “why” question until you’ve done it five times. For example, if someone injured themselves on an assembly line, the answer to the first “why” might be because the person got his or her hand stuck in the machine. Why did the person get his or her hand stuck? The employee didn’t pay attention to where he or she put the hand down. Why didn’t the person pay attention? The employee had been working for 10 hours straight and felt tired. Why was the person working for that long? The company is short staffed. Why? The company cut costs by firing essential workers to provide bigger bonuses to executives. Now, you’ve gotten to the root of the problem and can work to fix it.

Another way to use the “why” question is with a “challenge map.” If you feel uncertain about the problem, try asking why you want to solve it in the first place. Say a company wanted to outdo their competitors by copying their striped bar of soap. Yet, after making a replica, no one wanted to buy it. The design team didn’t discover why until they looked into the reasons people preferred one type of soap to another. The challenge was not how to sell the same soap better, but what characteristics of bathing, such as feeling fresh like the ocean, make people want to buy soap. Upon redefining the issue and making a sea-themed soap, with stripes, the team sold millions.

If you still feel stumped, look to your own perspective on the problem. If you don’t test your product or service out yourself, you end up relying on the opinions of others to guide your decisions. You need to experience the problem firsthand to make sure you solve the right one.

Prototype and experiment with your design.

Now that you thoroughly understand your customers and have identified the right problem, start solving. It’s good to think big, at first, when picturing solutions. For instance, when designer Eero Saarinen came to Australia to pick the design for the Sydney Opera House, a team had laid out many decent designs on the table for him to see. However, the design he picked was one he found in the waste bin that he claimed was far better than the rest. The team responded that they had thought that design was too “far out.” Saarinen replied that that was the point. There are usually ways to make a “far out” idea work, but not many ways to make a mediocre idea better. So aim high when envisioning possibilities.

Come up with as many solutions as you can think of, at first. As you go, you will most likely notice

other problems that need addressing. For example, a father noticed his daughter staying up really late at night to talk to her overseas friends who were in a different time zone. As the dad and daughter brainstormed ways to fix this, he recognized that her friends also needed to make a sacrifice on their part in terms of skipping some sleep. His daughter couldn’t be the only one who stayed up late or got up early. Once you have a list of solutions, narrow them down to the one you think will work best. In this case, the solution was to develop a schedule for the daughter and her friends’ calls.

Next, start testing out your solution through experimentation. For example, if you want your office to stop using Styrofoam cups for coffee, and your solution involves people using ceramic cups instead, put ceramic mugs by the coffee maker to see if anyone uses them. Maybe, at first, some people use them, but you quickly realize that no one wants to wash their mug and that you’ve now angered the janitor who has to clean up the mess. You have learned that your proposed solution doesn’t work, and you need to start over.

“A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” (Writer and poet Antoine de Saint-Exupéry)

Designing takes a lot of tries to get right, so don’t feel discouraged if your first solution doesn’t work. Keep circling back through the process until you get it right.